Files

Download Full Text (1.2 MB)

Publication Date

Spring 4-10-2015

Year of Release

2015

Note(s)

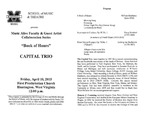

Capital Trio

In memory of Frank Glazer (1915-2015)

The Capital Trio came together in 1997 for a concert commemorating the one hundredth anniversary of the death of Brahms. Since that time they have performed in New England, New York, the Midwest, the South, and in Europe. They have participated in Summer Festivals in Maine and Michigan and held university residencies at Williams College, Long Island University, Bates College, SUNY Oswego, and Clark University. Their recording A Book of Hours, music of William Matthews, was released on Albany Records in 2010 (TROY 1239), and their second recording for Albany Records, music of David Walther, came out in 2013 (TROY 1428). Concerts this season include performances in Ohio, West Virginia, New York, Maine, and Boston. The Capital Trio has been chamber ensemble in residence at the University at Albany since 2008 and they would like to thank Joan Wick-Pelletier for her encouragement and support.

Duncan J. Cumming received degrees from Bates College and New England Conservatory and studied at the European Mozart Academy in Prague. In 2003 he received the Doctor of Musical Arts degree from Boston University. He joined the faculty at the University at Albany in 2006 and in 2010 he was honored to receive the College of Arts and Sciences Dean's Award for Outstanding Teaching. His book The Fountain of Youth: The Artistry of Frank Glazer was published in 2009. His recordings include a solo recording for Centaur (CRC 3125) including music of Brahms, Debussy, Satie, and Chopin and the chamber music recording A Book of Hours for Albany Records (TROY 1239). Recently two new recordings were released: Threads of the Heart, a chamber recording for Albany Records, and a historical instrument recording for Centaur (CRC 3231) of the music of Carl Maria von Weber on Weber's own 1815 Brodmann fortepiano. In concert and in recording he has collaborated with the mezzo soprano Magdelena Kozena, the conductor and keyboard player Christopher Hogwood, and pianist Frank Glazer. He has performed throughout the United States and Europe, most recently in Denmark, France, Switzerland, England, and Scotland. From 2002-2008 Cumming was on the faculty of the Boston University Tanglewood Institute. Before accepting the position at the University at Albany he was a member of the faculty at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts. He is the pianist of the Capital Trio and lives in New York with his wife, the violinist Hilary Walther Cumming, and his children Lucy, Mairi, and Bear.

Violinist Hilary Walther Cumming teaches at the University at Albany and performs as the violinist in the Capital Trio with pianist Duncan Cumming and cellist Şölen Dikener. Before moving to New York, she served as concertmaster of the Cape Cod Sinfonietta and the Andover Chamber Orchestra; she has been heard as soloist with these ensembles as well as with the Reading Symphony, Concord Orchestra, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra. A versatile artist, she is comfortable in many styles including classical, baroque, and Irish traditional music. Ms. Cumming graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree from Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois, where she studied with Gerardo Ribeiro. In 1991 she moved to Bloomington, Indiana, and earned a Master’s Degree under the tutelage of Franco Gulli, modern violin, and Stanley Ritchie, baroque violin at Indiana University. Upon graduation she was awarded a Fulbright grant, and she spent the next year in Copenhagen, Denmark, studying at the Royal Conservatory of Music with Peder Elbaek and Marta Libalova. During this time she traveled bi-monthly to Paris for lessons with Sylvie Gazeau and Nell Gotkovsky. Ms. Cumming has participated in concerts worldwide, and recently toured England, France, and Switzerland with the Capital Trio. She has recorded with the Capital Trio, the ATHELAS Ensemble (Denmark), The Abbott Trio, and the Coleridge Ensemble, among others.

Program Notes

A Book of Hours began as three movements: "L'après-midi d'un Arnold," "Le Tombeau de Monk," and "Morning Song." The composer explained that, as with the Roman Catholic Prayer Book, he was writing music for specific hours in the day. Two years later Matthews added two new movements: "Evensong" and "Fish Fry," to reflect early and late evening. Finally a sixth movement was added, "Catbird at Matins," based on a birdsong he heard early each morning from his window. At this point the six movements were reordered to reflect the chronology of the day, and the Capital Trio recorded the complete work for Albany Records (TROY 1239) for a CD that came out in 2010. "Catbird at Matins," while included on the recording, has never been performed and receives its premiere performance in these concerts. Here are the composer's notes (and biography) from the CD: A Book of Hours is a secular take on Medieval illustrated manuscripts of prayers and devotions appropriate to the cycle of six religious services observed in a day.

1. Catbird at Matins began as a transcription of an especially loud catbird fond of perching in a treetop outside my Maine bedroom window to sing every morning starting promptly and reliably at 4am.

2. Morning Song is for, by, and of the caffeinated.

3. L 'après-midi d'Arnold Sch _ was inspired by a photograph on a colleague's office door of the fearsome Viennese master himself, lolling on a Los Angeles beach in bathing trunks. Anton W drops by during a sleepy reverie in the warm sun.

4. Evensong is a peaceful twilight hymn without words.

5. Friday Night Fish Fry (Uneven Song) is a crooked take on Franco-American fiddle music as played in Maine.

6. Le tombeau de Monk is in memory of the great American composer and pianist, an upside-down take on his famous tune "Round Midnight."

A Book of Hours was composed for the members of the Capital Trio.

William Matthews (b. 1950, Toledo, Ohio) began studying and performing music as a flutist in Springfield, Ohio, then studied composition formally at Oberlin Conservatory (Coleman, Moore, Aschaffenburg), the University of Iowa (Hervig, Jenni, Hibbard), the Institute of Sonology in The Netherlands (Koenig, Laske), and the Yale School of Music (Druckman, Penderecki, Kramer). Awards and prizes include three BMI Awards to Student Composers, a Charles Ives Fellowship, a study abroad grant from IIE, two CRI recording awards from ACA, an Oberlin alumni fellowship, an NEA individual composer/librettist grant, and a summer seminar fellowship from the NEH. He has taught at Bates College in Maine since 1978, and currently serves as the Alice Swanson Esty Professor of Music. He considers himself a 'small-town composer' and often composes for local musicians and audiences, in a number of different styles. He divides his creative time between acoustic and electro-acoustic composition, the latter sometimes with video elements. He often composes music for dance.

Franz Schubert's Impromptu in C minor, Op. 90 No. 1 for solo piano has been added to this program in memory of Frank Glazer, 1915-2015. After my first piano lesson with Mr. Glazer, in 1986, I immediately raced off to a quiet place to take down notes about what I had learned. I continued to do this, more often than not in my cold pick-up truck at an empty parking lot near his house, lest I should forget anything he said on the drive home. As I leaf through these notebooks, which eventually numbered over 2,000 pages, I find his advice to me about this Schubert piece on the first lesson I had with him about it. The opening chord, he said, is to get everyone's attention. It should say, "Listen, I'm going to tell a story. Once upon a time ... and the story begins." At the end he said, "It ends with a certain sense of hopefulness, wistfulness ... and what a great story it was." That's how I feel about his nearly 100 years. What a great story it was.

Beethoven's Trio in D major, Op. 70 No. 1, is known as the "Geister Trio," or "Ghost Trio," and it was so named because of the mysterious nature of the second movement. Beethoven's teacher, Franz Joseph Haydn, made the combination of piano, violin, and cello famous with his 30 works in this genre, but in his hands it was essentially a glorified piano sonata where the violin and cello mostly doubled the pianist's lines. The violin liberated itself first, but the role of the cello in early classical trios was largely that of a basso continua instrument. Beethoven, supporter as he was of the French Revolution, was not surprisingly more democratic in his distribution of melody among the parts. Cellists have come a long way since the days of Haydn. Of course the irony here is that Haydn wrote two famous cello concertos, but nevertheless he didn't wrestle the cellist free from his conventional role in the piano trio. He left that to Beethoven and his successors.

Beethoven's very first published work, Op. 1, was a set of three trios for piano, violin, and cello. He wrote two more trios with clarinet in place of violin (one was an arrangement of another work) in the next few years and then didn't return to the medium until 1808 with two trios, Op. 70, of which this is the first. Beethoven's student (and composer of endless exercises for pianists) Carl Czerny said the spooky second movement made him think of the ghost scene from Hamlet, but most people today associate it with Macbeth. Maybe the title should be "Witch Trio," as Beethoven was sketching an opera about Macbeth at the time (an endeavor he later abandoned). The first movement is a compact sonata-allegro form movement, quite classical in style when one considers that it follows the fifth and sixth symphonies as well as many other works from the so called "Heroic" period. After a unison opening spanning four octaves the first soaring melody is taken up by the cello. This featuring of the cello melodically at all, let alone so soon in the piece, seems a direct attack on his former teacher Haydn's method of piano trio writing, but in fact by this time Beethoven had already written three sonatas for cello and piano as well as three variation sets for the same combination, not to mention the "Triple Concerto" for piano, violin, and cello with orchestra which features the cello prominently.

The "Ghost" movement begins almost as if it's standing still. The first two notes, played only in the strings, are mere quarter notes, although they sound like whole notes. With a barely discernable pulse at first, the movement explores eerie, hollow sounds, especially in the strings, and tremolos like flickering candles haunt the piano part; the overall mood is better experienced than described so I' II say no more about it here. In the third movement the piano jumps off to a racing start, or so we think before the strings come in and apply the brakes. The three together try again, but like a car that won't turn over, the second time yields no more success than the first. But this engine does eventually start, and when it does it seems it will never stop again. The last movement is the longest (at least in measures and pages, if not in time). Before it does manage to end, it first begins to sound like a broken record, when in fact each chord is changing ever so slightly in the piano under pizzicato (plucking) strings. The spelling undergoes a change so that F sharp becomes G flat-these are of course the same note on the piano and sound the same when struck but are notated differently on the printed page. To those who don't read music this is probably best explained as the musical equivalent of a homonym-things that sound the same but are spelled differently. This move to F-sharp leads finally to the dominant and the end. As was becoming more and more typical of Beethoven at this time, the focus no longer seems to be on the first movement. The second is particularly serious in this trio, and the last is not only the largest, but as is the case in the "Moonlight" Sonata and the Fifth Symphony, is in sonata-allegro form rather than a more typical last movement form (like rondo form). Perhaps Beethoven was finding rondo form insufficient for the weight he intended to give his new finales. As he added more length and significance to his last movements, he often wrote them in different forms. By the end of his life (the last three piano sonatas, the Ninth Symphony) we find mostly fugues and variation movements for finales. Another similarity to the Fifth Symphony in this movement is the interruption of the flow with a sudden short cadenza in the piano, much like the oboe solo that appears in the recapitulation of the first movement of the Fifth Symphony. The difference here is it appears in both the exposition and the recapitulation. E.T.A. Hoffmann, famous writer and critic (who wrote the Nutcracker and was known for his "Ghost" stories as well), had this to say about the Op. 70 trios:

There is in these trios, in terms of mere dexterity and breakneck passages up and down the keyboards with both hands, executing all sorts of odd leaps and whimsical flourishes, no great difficulty in the piano part, at all, since the few runs, triplet figures and the like must be within the powers of any practised player: and yet, their performance is extremely difficult. Many a so-called virtuoso dismisses Beethoven's piano works, not only complaining 'Very difficult!' but adding 'And most ungrateful!'--As far as difficulty is concerned, the proper, comfortable performance of Beethoven's works requires nothing less than that one understands him, that one penetrates deeply into his inner nature, and that one, in the knowledge of one's own state of grace, ventures boldly into the circle of magical beings that his powerful spell summons forth.

Note

First Presbyterian Church, Huntington, WV

Disciplines

Arts and Humanities | Fine Arts | Music | Music Performance

Recommended Citation

Marshall University, "Marshall University Music Department Presents Music Alive Faculty & Guest Artist, Collaboration Series, "Book of Hours", Capital Trio" (2015). All Performances. 698.

https://mds.marshall.edu/music_perf/698